Limitações da psiquiatria biomédica Controvérsias entre psiquiatras conservadores e reforma psiquiátrica Psiquiatria não comercial e íntegra Suporte para desmame de drogas psiquiátricas Concepções psicossociais Gerenciamento de benefícios/riscos dos psicoativos Acessibilidade para Deficiência psicossocial Psiquiatria com senso crítico Temas em Saúde Mental Prevenção quaternária Consumo informado Decisão compartilhada Autonomia "Movimento" de ex-usuários Alta psiquiátrica Justiça epistêmica

Pacientes produtores ativos de saúde (prosumo)

Essa avalanche de informações e conhecimento relacionada à saúde e despejada todos os dias sobre os indivíduos sem a menor cerimônia varia muito em termos de objetividade e credibilidade. Porém, é preciso admitir que ela consegue atrair cada vez mais a atenção pública para assuntos de saúde - e muda o relacionamento tradicional entre médicos e pacientes, encorajando os últimos a exercer uma atitude mais participativa na relação.

Ironicamente, enquanto os pacientes conquistam mais acesso às informações sobre saúde, os médicos têm cada vez menos tempo para estudar as últimas descobertas científicas ou para ler publicações da área - on-line ou não -, e mesmo para se comunicar adequadamente com especialistas de áreas relevantes e/ou com os próprios pacientes.

Além disso, enquanto os médicos precisam dominar conhecimentos sobre as diferentes condições de saúde de um grande número de pacientes cujos rostos eles mal conseguem lembrar, um paciente instruído, com acesso à internet, pode, na verdade, ter lido uma pesquisa mais recente do que o médico sobre sua doença específica.

Os pacientes chegam ao consultório com paginas impressas contendo o material que pesquisaram na internet, fotocópias de artigos da Physician's Desk Reference, ou recorte de outras revistas e anuários médicos. Eles fazem perguntas e não ficam mais reverenciando a figura do médico, com seu imaculado avental branco.

Aqui as mudanças no relacionamento com os fundamentos profundos do tempo e conhecimento alteraram completamente a realidade médica.

Livro: Riqueza Revolucionária - O significado da riqueza no futuro

Aviso!

Aviso!

A maioria das drogas psiquiátricas pode causar reações de abstinência, incluindo reações emocionais e físicas com risco de vida. Portanto, não é apenas perigoso iniciar drogas psiquiátricas, também pode ser perigoso pará-las.

Retirada de drogas psiquiátricas deve ser feita cuidadosamente sob supervisão clínica experiente. [Se possível] Os métodos para retirar-se com segurança das drogas psiquiátricas são discutidos no livro do Dr. Breggin: A abstinência de drogas psiquiátricas: um guia para prescritores, terapeutas, pacientes e suas famílias.

Observação: Esse site pode aumentar bastante as chances do seu psiquiatra biológico piorar o seu prognóstico, sua família recorrer a internação psiquiátrica e serem prescritas injeções de depósito (duração maior). É mais indicado descontinuar drogas psicoativas com apoio da família e psiquiatra biológico ou pelo menos consentir a ingestão de cápsulas para não aumentar o custo do tratamento desnecessariamente.

Observação 2: Esse blogue pode alimentar esperanças de que os familiares ou psiquiatras biológicos podem mudar e começar a ouvir os pacientes e se relacionarem de igual para igual e racionalmente.

A mudança de familiares e psiquiatras biológicos é uma tarefa ingrata e provavelmente impossível.

https://breggin.com/the-reform-work-of-peter-gotzsche-md/

segunda-feira, 27 de fevereiro de 2017

Ciência vive uma epidemia de estudos inúteis

http://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/01/10/internacional/1484073680_523691.html?id_externo_rsoc=Fb_BR_CM

Reasons not to believe in lithium

https://joannamoncrieff.com/2015/07/01/reasons-not-to-believe-in-lithium/

‘I don’t believe in God, but I believe in lithium’ is the title of

Jamie Lowe’s moving account of her manic depression (now usually

referred to as bipolar disorder) in the New York Times (http://mobile.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/magazine/i-dont-believe-in-god-but-i-believe-in-lithium.html?referrer=).

The piece reminds us how devastating and frightening this condition can

be, so it is understandable that the author put her faith in the

miracle cure psychiatrists have been recommending since the 1950s:

lithium.

Lowe took lithium from the age of 17 for 20 years, until at the age of 37 or thereabouts she was diagnosed with kidney failure, a direct result of this treatment. She will need dialysis, and a kidney transplant – a high price to pay for a really effective treatment. The sad thing is, we have little evidence that lithium is a really effective treatment, or even that it is effective at all. However, as I explain below, once someone starts on lihium, there is evidence that there is a high risk of having a relapse if they stop it. This is not the same as showing that lithium is a good thing in the first place, but it does mean that people who are already taking lithium have to be very careful if they decide they want to come off.

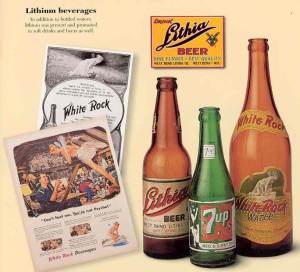

Lithium is a neurotoxin. It inhibits the functioning of the nervous system so that people typically feel drowsy, lethargic and slowed up. These effects were observed in guinea pigs initially, and then in people with mania by the Australian doctor, John Cade, who first proposed that lithium might be a useful treatment for manic depression (1). In the 19th century lithium had been used for the treatment of gout, and became a popular ingredient of tonics and even beer, until it was shown that it did not dissolve the uric acid crystals that cause gout as had been claimed (2).

The sedative and slowing effects of lithium, although usually described as side effects, account for why lithium can help reduce arousal and activity levels in people with acute manic symptoms. So there is nothing magic or specific about lithium’s action in manic depression. Lithium will exert its characteristic effects in anyone, whether or not they have mania or manic depression. In theory, these effects might suppress the emergence of a manic episode, as well as reduce the severity of symptoms once an episode has started. The evidence that long-term lithium treatment reduces the occurrence of manic or depressive episodes is actually very weak, however.

The main problem with the evidence is that there is no study in which people who have been started on lithium have been compared with people who haven’t. Every randomised trial of lithium versus placebo starts with people who are already on drug treatment of one sort or another, often lithium itself. Now there is good evidence, accepted by leading proponents of lithium (3;4), that withdrawing from lithium can precipitate a relapse of manic depression, especially a manic episode. Three studies have shown, for example, that people are more likely to have a relapse after stopping lithium than they were before they started it (5-7). No one knows the mechanism for this, but it is as if removing the neurological suppression produced by lithium causes the nervous system of a susceptible person to go into over-drive, precipitating a manic relapse.

So demonstrating that people who stop lithium and start a placebo have higher rates of relapse than people who continue on lithium does not demonstrate that going onto lithium in the first place prevents episodes. But all the placebo-controlled trials of lithium are like this to at least some degree. The trial that established the idea of long-term lithium treatment, for example, started with people who had already been on lithium for many years (8). In more recent studies, not all participants have been on lithium prior to enrolment, but those not taking lithium were likely to be taking other sorts of sedative medication. The first of these recent studies, the largest study up until that point involving 372 participants, found no difference between lithium, sodium valproate and placebo in terms of the rate of recurrence of any type of mood episode (9). The second found a higher rate of manic relapse in placebo-treated patients compared with those on lithium, but the pattern with which relapses occurred was strongly suggestive of a discontinuation effect. A large majority of relapses occurred in the first few weeks after allocation to placebo, and none occurred in the last few months of the study, suggesting that the point of discontinuation of previous medication was associated with subsequent relapses (10). In the final trial, rates of mania were higher in people on placebo by about 14% (14% vs 28%), but 20% of participants were taking lithium before randomisation, and still others were taking Depakote or antipsychotics, all of which were stopped relatively abruptly prior to the trial (11).

The possibility that relapses in the placebo groups in these trials are induced by withdrawal of previous medication would make sense of the fact that it has proved impossible to demonstrate that people receiving modern drug treatment for manic depression do any better than those who don’t, or didn’t. In fact, overall, they seem to do slightly worse.

Two important studies have examined rates of relapse in people with classical manic depressive symptoms prior to the 1950s. American psychiatrist George Winokur found the records of 100 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital between 1934 and 1944 with an episode of mania and then followed them up through their hospital records. He found that 48% had a relapse requiring hospitalisation over an average follow-up duration of 3.2 years. For comparison purposes this equates to a relapse rate of 15% per year (12). Margaret Harris, David Healy and colleagues did the same for patients admitted to the North Wales asylum in the 1890s. They found that, on average, patients had 4 relapses over the subsequent 10 years, equating to a relapse rate of 20% a year. In comparison, during the 1990s, people with manic depression (most of whom we can assume were on drug treatment) were having an average of 6.3 admissions in 10 years, or 31% per year, for example (13). That’s over 10% higher than the rate of admission for people in the 1890s!

Relapse rates among patients taking lithium in randomised trials that have started with patients experiencing a manic episode (as the historical studies did) are uniformly higher too. In the comparison between lithium, Divalproex (Depakote) and placebo, for example, the lithium group relapsed at a rate of 31% a year (9). In the comparison between lithium, lamotrigine and placebo in people with mania it was 26% a year (10). Admittedly these figures include all relapses, and not just those severe enough to require hospitalisation. A large study conducted in the 1970s, however, found that rates of hospital admission for relapse were 21.5% per year in the lithium group (14).

Several ‘naturalistic’ studies have tracked the progress of people taking lithium and other treatments. The vast majority of these studies also show high relapse rates among those on lithium, even though most studies highly compliant populations and we know that people who are compliant with any treatment (including placebo) have better outcomes than those who are not. One study of patients who were known to be compliant with their lithium treatment for at least a year, for example, found a rate of relapse of 40% a year over a 6 year follow-up (15).

In my view the evidence that lithium helps prevent episodes of manic depression is far too weak to outweigh the harms it can cause (which commonly include thyroid damage, kidney damage, and acute neurological toxicity at doses very close to those used in practice, hence the need for blood monitoring). Manic depression is a highly variable condition. Some people have many episodes, some people few, and the pattern of episodes varies throughout life as well. Long periods of remaining well are not necessarily evidence of a treatment’s effectiveness. What we would need to demonstrate the efficacy and value of lithium is a prospective randomised trial in which people who had not previously been on long-term drug treatment were randomly allocated to start lithium or placebo. At present, my view is that the evidence that lithium might be effective is not strong enough to justify such a trial, given the health risks associated with it.

As Jamie Lowe eloquently expresses, manic depression can be a terrifying condition, and I know that people will say therefore ‘if not lithium, then what?’. But the evidence that any long-term drug treatment is better than nothing is not strong (1). Many doctors and patients are very uncomfortable with that conclusion, and feel there just has to be something. And if people want to try some sort of drug treatment, like antipsychotics or anticonvulsants, then I feel that doctors should help them take it as safely as possible, at as low a dose as possible. But doctors should be honest about the state of the evidence and for lithium, I am not convinced there are any circumstances that justify the risks it entails.

In 1957 a pharmacologist bemoaned the fashion for treatment ‘by lithium poisoning’ (16). One day, I believe, we will wake up and realise his concern was spot on!

Reference List

(1) Moncrieff J. The Myth of the Chemical Cure: a critique of psychiatric drug treatment. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008.

(2) Johnson FN. The History of Lithium Therapy. London: Macmillan; 1984.

(3) Franks MA, Macritchie KAN, Young AH. The consequences of suddenly stopping psychotropic medication in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 2005;4(1):11-7.

(4) Goodwin GM. Recurrence of mania after lithium withdrawal. Implications for the use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994 Feb;164(2):149-52.

(5) Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Viguera AC. Discontinuing lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders: risks and implications. Bipolar Disord 1999 Sep;1(1):17-24.

(6) Suppes T, Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Tohen M. Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991 Dec;48(12):1082-8.

(7) Cundall RL, Brooks PW, Murray LG. A controlled evaluation of lithium prophylaxis in affective disorders. Psychol Med 1972 Aug;2(3):308-11.

(8) Baastrup PC, Poulsen JC, Schou M, Thomsen K, Amdisen A. Prophylactic lithium: double blind discontinuation in manic-depressive and recurrent-depressive disorders. Lancet 1970 Aug 15;2(7668):326-30.

(9) Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000 May;57(5):481-9.

(10) Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M, et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003 Apr;60(4):392-400.

(11) Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Behnke K, Mehtonen OP, et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003 Sep;64(9):1013-24.

(12) Winokur G. The Iowa 500: heterogeneity and course in manic-depressive illness (bipolar). Compr Psychiatry 1975 Mar;16(2):125-31.

(13) Harris M, Chandran S, Chakraborty N, Healy D. The impact of mood stabilizers on bipolar disorder: the 1890s and 1990s compared. Hist Psychiatry 2005 Dec;16(pt 4 (no 64)):423-34.

(14) Prien RF, Caffey EM, Jr., Klett CJ. Prophylactic efficacy of lithium carbonate in manic-depressive illness. Report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health collaborative study group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973 Mar;28(3):337-41.

(15) Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Floris G. Long-term clinical effectiveness of lithium maintenance treatment in types I and II bipolar disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001 Jun;41:s184-s190.

(16) Wikler A. The Relation of Psychiatry to Pharmacology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co; 1957.

Reasons not to believe in lithium

Lowe took lithium from the age of 17 for 20 years, until at the age of 37 or thereabouts she was diagnosed with kidney failure, a direct result of this treatment. She will need dialysis, and a kidney transplant – a high price to pay for a really effective treatment. The sad thing is, we have little evidence that lithium is a really effective treatment, or even that it is effective at all. However, as I explain below, once someone starts on lihium, there is evidence that there is a high risk of having a relapse if they stop it. This is not the same as showing that lithium is a good thing in the first place, but it does mean that people who are already taking lithium have to be very careful if they decide they want to come off.

Lithium is a neurotoxin. It inhibits the functioning of the nervous system so that people typically feel drowsy, lethargic and slowed up. These effects were observed in guinea pigs initially, and then in people with mania by the Australian doctor, John Cade, who first proposed that lithium might be a useful treatment for manic depression (1). In the 19th century lithium had been used for the treatment of gout, and became a popular ingredient of tonics and even beer, until it was shown that it did not dissolve the uric acid crystals that cause gout as had been claimed (2).

The sedative and slowing effects of lithium, although usually described as side effects, account for why lithium can help reduce arousal and activity levels in people with acute manic symptoms. So there is nothing magic or specific about lithium’s action in manic depression. Lithium will exert its characteristic effects in anyone, whether or not they have mania or manic depression. In theory, these effects might suppress the emergence of a manic episode, as well as reduce the severity of symptoms once an episode has started. The evidence that long-term lithium treatment reduces the occurrence of manic or depressive episodes is actually very weak, however.

The main problem with the evidence is that there is no study in which people who have been started on lithium have been compared with people who haven’t. Every randomised trial of lithium versus placebo starts with people who are already on drug treatment of one sort or another, often lithium itself. Now there is good evidence, accepted by leading proponents of lithium (3;4), that withdrawing from lithium can precipitate a relapse of manic depression, especially a manic episode. Three studies have shown, for example, that people are more likely to have a relapse after stopping lithium than they were before they started it (5-7). No one knows the mechanism for this, but it is as if removing the neurological suppression produced by lithium causes the nervous system of a susceptible person to go into over-drive, precipitating a manic relapse.

So demonstrating that people who stop lithium and start a placebo have higher rates of relapse than people who continue on lithium does not demonstrate that going onto lithium in the first place prevents episodes. But all the placebo-controlled trials of lithium are like this to at least some degree. The trial that established the idea of long-term lithium treatment, for example, started with people who had already been on lithium for many years (8). In more recent studies, not all participants have been on lithium prior to enrolment, but those not taking lithium were likely to be taking other sorts of sedative medication. The first of these recent studies, the largest study up until that point involving 372 participants, found no difference between lithium, sodium valproate and placebo in terms of the rate of recurrence of any type of mood episode (9). The second found a higher rate of manic relapse in placebo-treated patients compared with those on lithium, but the pattern with which relapses occurred was strongly suggestive of a discontinuation effect. A large majority of relapses occurred in the first few weeks after allocation to placebo, and none occurred in the last few months of the study, suggesting that the point of discontinuation of previous medication was associated with subsequent relapses (10). In the final trial, rates of mania were higher in people on placebo by about 14% (14% vs 28%), but 20% of participants were taking lithium before randomisation, and still others were taking Depakote or antipsychotics, all of which were stopped relatively abruptly prior to the trial (11).

The possibility that relapses in the placebo groups in these trials are induced by withdrawal of previous medication would make sense of the fact that it has proved impossible to demonstrate that people receiving modern drug treatment for manic depression do any better than those who don’t, or didn’t. In fact, overall, they seem to do slightly worse.

Two important studies have examined rates of relapse in people with classical manic depressive symptoms prior to the 1950s. American psychiatrist George Winokur found the records of 100 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital between 1934 and 1944 with an episode of mania and then followed them up through their hospital records. He found that 48% had a relapse requiring hospitalisation over an average follow-up duration of 3.2 years. For comparison purposes this equates to a relapse rate of 15% per year (12). Margaret Harris, David Healy and colleagues did the same for patients admitted to the North Wales asylum in the 1890s. They found that, on average, patients had 4 relapses over the subsequent 10 years, equating to a relapse rate of 20% a year. In comparison, during the 1990s, people with manic depression (most of whom we can assume were on drug treatment) were having an average of 6.3 admissions in 10 years, or 31% per year, for example (13). That’s over 10% higher than the rate of admission for people in the 1890s!

Relapse rates among patients taking lithium in randomised trials that have started with patients experiencing a manic episode (as the historical studies did) are uniformly higher too. In the comparison between lithium, Divalproex (Depakote) and placebo, for example, the lithium group relapsed at a rate of 31% a year (9). In the comparison between lithium, lamotrigine and placebo in people with mania it was 26% a year (10). Admittedly these figures include all relapses, and not just those severe enough to require hospitalisation. A large study conducted in the 1970s, however, found that rates of hospital admission for relapse were 21.5% per year in the lithium group (14).

Several ‘naturalistic’ studies have tracked the progress of people taking lithium and other treatments. The vast majority of these studies also show high relapse rates among those on lithium, even though most studies highly compliant populations and we know that people who are compliant with any treatment (including placebo) have better outcomes than those who are not. One study of patients who were known to be compliant with their lithium treatment for at least a year, for example, found a rate of relapse of 40% a year over a 6 year follow-up (15).

In my view the evidence that lithium helps prevent episodes of manic depression is far too weak to outweigh the harms it can cause (which commonly include thyroid damage, kidney damage, and acute neurological toxicity at doses very close to those used in practice, hence the need for blood monitoring). Manic depression is a highly variable condition. Some people have many episodes, some people few, and the pattern of episodes varies throughout life as well. Long periods of remaining well are not necessarily evidence of a treatment’s effectiveness. What we would need to demonstrate the efficacy and value of lithium is a prospective randomised trial in which people who had not previously been on long-term drug treatment were randomly allocated to start lithium or placebo. At present, my view is that the evidence that lithium might be effective is not strong enough to justify such a trial, given the health risks associated with it.

As Jamie Lowe eloquently expresses, manic depression can be a terrifying condition, and I know that people will say therefore ‘if not lithium, then what?’. But the evidence that any long-term drug treatment is better than nothing is not strong (1). Many doctors and patients are very uncomfortable with that conclusion, and feel there just has to be something. And if people want to try some sort of drug treatment, like antipsychotics or anticonvulsants, then I feel that doctors should help them take it as safely as possible, at as low a dose as possible. But doctors should be honest about the state of the evidence and for lithium, I am not convinced there are any circumstances that justify the risks it entails.

In 1957 a pharmacologist bemoaned the fashion for treatment ‘by lithium poisoning’ (16). One day, I believe, we will wake up and realise his concern was spot on!

Reference List

(1) Moncrieff J. The Myth of the Chemical Cure: a critique of psychiatric drug treatment. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008.

(2) Johnson FN. The History of Lithium Therapy. London: Macmillan; 1984.

(3) Franks MA, Macritchie KAN, Young AH. The consequences of suddenly stopping psychotropic medication in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 2005;4(1):11-7.

(4) Goodwin GM. Recurrence of mania after lithium withdrawal. Implications for the use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994 Feb;164(2):149-52.

(5) Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Viguera AC. Discontinuing lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders: risks and implications. Bipolar Disord 1999 Sep;1(1):17-24.

(6) Suppes T, Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Tohen M. Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991 Dec;48(12):1082-8.

(7) Cundall RL, Brooks PW, Murray LG. A controlled evaluation of lithium prophylaxis in affective disorders. Psychol Med 1972 Aug;2(3):308-11.

(8) Baastrup PC, Poulsen JC, Schou M, Thomsen K, Amdisen A. Prophylactic lithium: double blind discontinuation in manic-depressive and recurrent-depressive disorders. Lancet 1970 Aug 15;2(7668):326-30.

(9) Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000 May;57(5):481-9.

(10) Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M, et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003 Apr;60(4):392-400.

(11) Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Behnke K, Mehtonen OP, et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003 Sep;64(9):1013-24.

(12) Winokur G. The Iowa 500: heterogeneity and course in manic-depressive illness (bipolar). Compr Psychiatry 1975 Mar;16(2):125-31.

(13) Harris M, Chandran S, Chakraborty N, Healy D. The impact of mood stabilizers on bipolar disorder: the 1890s and 1990s compared. Hist Psychiatry 2005 Dec;16(pt 4 (no 64)):423-34.

(14) Prien RF, Caffey EM, Jr., Klett CJ. Prophylactic efficacy of lithium carbonate in manic-depressive illness. Report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health collaborative study group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973 Mar;28(3):337-41.

(15) Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Floris G. Long-term clinical effectiveness of lithium maintenance treatment in types I and II bipolar disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001 Jun;41:s184-s190.

(16) Wikler A. The Relation of Psychiatry to Pharmacology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co; 1957.

quarta-feira, 22 de fevereiro de 2017

terça-feira, 21 de fevereiro de 2017

capítulos psiquiatria medicamentos mortais e crime organizado

capítulos psiquiatria medicamentos mortais e crime organizado

http://www.mediafire.com/file/ey3ds1qv5cmoilr/medicamentos++mortais+e+crime+organizado+psiquiatria.pdf

http://www.mediafire.com/file/ey3ds1qv5cmoilr/medicamentos++mortais+e+crime+organizado+psiquiatria.pdf

tradução história dos antipsicóticos

Tradução A história problemática dos antipsicóticos

http://www.mediafire.com/file/ra81839qzeqh44c/A+p%C3%ADlula+mais+amarga.+A+hist%C3%B3ria+problem%C3%A1tica+dos+antipsic%C3%B3ticos.doc

http://www.mediafire.com/file/ra81839qzeqh44c/A+p%C3%ADlula+mais+amarga.+A+hist%C3%B3ria+problem%C3%A1tica+dos+antipsic%C3%B3ticos.doc

sexta-feira, 17 de fevereiro de 2017

Viewing addiction as a brain disease promotes social injustice

http://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-017-0055

Viewing addiction as a brain disease promotes social injustice

The

view of drug use and drug addiction as a brain disease serves to

perpetuate unrealistic, costly, and discriminatory drug policies, argues

Carl L. Hart.

More

than 25 years ago, I began studying neuroscience because I thought this

approach would uniquely fix the ‘drug problem’. At that time, I

believed that the poverty and crime in the resource-poor community from

which I came was a direct result of drug addiction; so, I reasoned that

if I could cure addiction, especially through neural manipulations, I

could fix the poverty and crime in my community. But, I learned that

while cocaine — and other recreational drugs — temporarily alters the

functioning of specific neurons in the brains of all who ingest the

drug, the vast majority of users never become addicted. And regarding

the relatively small percentage of individuals who do become addicted,

co-occurring psychiatric disorders and socioeconomic factors account for

a substantial proportion of these addictions. To date, there has been

no identified biological substrate to differentiate non-addicted persons

from addicted individuals.

The

notion that drug addiction is a brain disease is catchy but empty:

there are virtually no data in humans indicating that addiction is a

disease of the brain, in the way that, for instance, Huntington's or

Parkinson's are diseases of the brain. With these illnesses, one can

look at the brains of affected individuals and make accurate predictions

about the disease involved and their symptoms.

We

are nowhere near being able to distinguish the brains of addicted

persons from those of non-addicted individuals. Despite this, the

‘diseased brain’ perspective has outsized influence on research funding

and direction, as well as on how drug use and addiction are viewed in

society. For example, the recently initiated multimillion-dollar

Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development longitudinal study (https://addictionresearch.nih.gov/abcd-study)

primarily seeks to gather neuroimaging data to better understand drug

use and addiction among adolescents. It collects genetic information and

measures drug use and academic achievement but lacks careful

consideration of important social factors. Notably, there has never been

such an ambitious funding effort focused on psychosocial determinants

or consequences (for example, employment status, racial discrimination,

neighbourhood characteristics, policing) of drug use or addiction.

This

situation contributes to unrealistic, costly, and harmful drug

policies. If the real problem with drug addiction, for example, is the

interaction between the drug itself and an individual's brain, then the

solution to this problem lies in one of two approaches. Either remove

the drug from society through policies and law enforcement (for example,

drug-free societies) or focus exclusively on the ‘addicted’

individual's brain as the problem. In both cases, there is neither need

for nor interest in understanding the role of socioeconomic factors in

maintaining drug use or mediating drug addiction.

The

detrimental effects of using law enforcement as a primary means to deal

with drug use are well documented. Millions are arrested annually for

drug possession and the abhorrent practice of racism flourishes in the

enforcement of such policies. In the United States, for example,

cannabis possession accounts for nearly half of the 1.5 million annual

drug arrests, and blacks are four times more likely to be arrested for

cannabis possession than whites, even though both groups use cannabis at

similar rates.

An

insidious assumption of the diseased brain theory is that any use of

certain drugs is considered pathological, even the non-problematic,

recreational use that characterizes the experience of the overwhelming

majority who ingest these drugs. For example, in a popular US anti-drug

campaign, it is implied that one hit of methamphetamine is enough to

cause irrevocable damage: http://www.methproject.org/ads/tv/deep-end.html.

In

the 1980s, crack cocaine use was blamed for everything from extreme

violence to high unemployment rates, premature death, and child

abandonment. Even more frightening, addiction to the drug was said to

occur after only one hit. Drug experts with neuroscience leanings

weighed in. “The best way to reduce demand”, Yale University psychiatry

professor Frank Gawin was quoted to say in Newsweek (16 June 1986),

“would be to have God redesign the human brain to change the way cocaine

reacts with certain neurons.”

‘Neuro’

remarks made about drugs with no foundation in evidence were

pernicious: they helped to shape an environment in which there was an

unwarranted and unrealistic goal of eliminating certain types of drug

use at any cost to marginalized citizens. In 1986, the US Congress

passed legislation setting penalties that were literally 100 times

harsher for crack than for powder cocaine violations. More than 80% of

those sentenced for crack cocaine offences are black, despite the fact

that the majority of users of the drug are white. Today, many find the

crack/powder laws repugnant because they exaggerate the harmful effects

of crack and are enforced in a racially discriminatory manner, but few

critically examine the role played by the scientific community in

propping up the assumptions underlying these laws.

For

their part, the scientific community has virtually ignored the shameful

racial discrimination that occurs in drug law enforcement. The

researchers themselves are overwhelmingly white and do not have to live

with the consequences of their actions. I don't have this luxury. Every

time I look into the faces of my children or go back to the place of my

youth, I am forced to face the decimation that results from the racial

discrimination that is so rampant in the application of drug laws and is

abetted by arguments poorly grounded in scientific evidence.

We

can no longer allow neuro-exaggerations to determine our drug research

funding priorities and directions, shape our views on drugs, nor our

drug policies. The stakes are too high and the human cost is

incalculable.

Author information

Affiliations

Carl L. Hart is the Dirk Ziff Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychology, and Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University, Box 120, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, New York 10032, USA.

- Carl L. Hart

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carl L. Hart.

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)